Many of the materials that go into the making of a book are flat: paper, board, bookcloth. Of course, all of these things, including the finished book, are at least three dimensional. But have you ever heard of a book being round? A-round, sure… for some of us more than others. But really, truly, round? In my work repairing old books, I have seen many a round book, meaning the book is no longer a book per se–it has become a receptacle. This is most often the case with family Bibles, but it happens to other books as well.

I recently had the opportunity to repair one such book for a class I taught in book repair. I usually shop for books for students to repair at Friends of the Library sales, and that was where I found The Complete Poems of Paul Laurence Dunbar. I wanted to write about my work on this book for several reasons, the primary one being that people are often surprised at what I do for a living, and don’t believe that books can in fact be repaired. As you will see here, even when a book has so many problems that they can’t all be repaired at once, the book’s condition can be so vastly improved as to make a huge difference to the future of it. I also wanted to write about this book because my work on it brought up some interesting issues in conservation I thought worth discussing. Finally, there were some things I learned while repairing this book that I wanted to share.

These informal photos taken prior to treatment may begin to give you an idea of what I mean when I say this book is a receptacle. In these four photos, we already see six newspaper clippings. And as I continued to observe the book’s condition, I came across many more clippings, pamphlets, three small pages of handwritten notes for a radio address, a church directory, and so on.

Paul Laurence Dunbar was born only seven years after the end of the Civil War. His parents had been slaves, so he was the first generation of free African-Americans in his family. He wrote poems, novels, and plays, some in dialect, some not. He died young of tuberculosis, dying well before the Harlem Renaissance gained steam. However, many writers from the Harlem Renaissance onward have cited Dunbar as an inspiration, and many feel that he was America’s earliest great African-American literary figure. It makes sense to me, in view of all this, that someone chose to place all their most important notes, desires for self-betterment, news articles on Wendell Willkie, and even Christmas greetings within this volume.

Something I happened to learn while I was repairing this book, through an unrelated string of concurrent events, was how a photogravure is made. Though common in image output generation in book production, I guess I never had the reason to study the making of photogravures before. Someone I know told me he had made some, and when I said I didn’t know what they were, he described them. At that point, I realized that the book I was working on contained one. A pretty nice one, I thought.

A photogravure is basically a way of using a film positive to burn an image into a copper plate suitable for use in printing with ink, combining photography with intaglio printing.

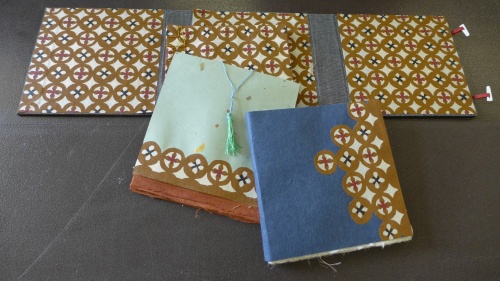

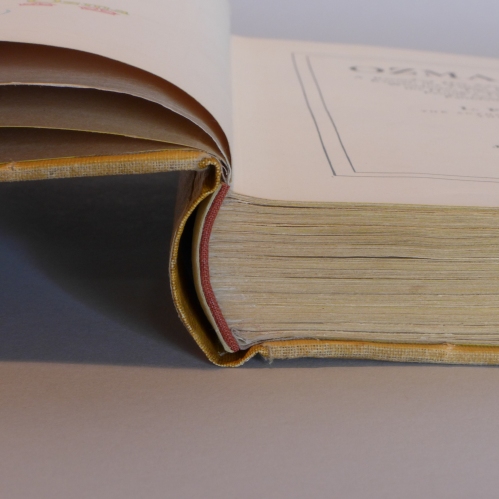

I’m happy with how my repair of this book came out–the book opens well, and all the pages have been stabilized. I’m even more pleased with the repairs completed by my students in the class. The students did so well we even had time to create protective four-flap enclosures for our books, so in my case, all the inclusions now have a contained place to reside that does not compromise the opening and closing of the book’s covers. However, there is one topic that is not addressed in the limited time available in that particular class: tape removal. Tape removal often requires the use of toxic solvents, requiring a vacuum table, a fume hood, and/or a fitted respirator: equipment and materials we do not have at SFCB. The Complete Poems of Paul Laurence Dunbar has several kinds of very old tape that are all causing various kinds of damage to the paper. The worst instance of this is on the reverse side of the lovely photogravure portrait.

There are many types of tape, and they all age in different ways and at different rates, causing different effects to the paper they’re stuck to. Some of the adhesives dry out and flake off or can be gently scraped off, as was the case with the opaque white tape on the inner front pastedown. Others melt into the fibers of the paper they’re stuck to and create an inextricable bond, and an irreversible stain. This process can take decades, but once it happens, there is not much to be done about it. Holding this page up to the light shows where the tape on the reverse side of this page is located, and where the stain might be headed.

Let this be, then, my one and only Public Service Announcement on Pressure-Sensitive Adhesive. Just say no, okay? It does not matter if the product says it’s archival. ‘Archival’ is an even vaguer marketing term than ‘organic’. Believe me, I understand the challenges of possessing an item in need of repair. The temptation to use a quick fix is strong. There are many book repair manuals out there that instruct on the use of tape–unfathomably. But, as common sense dictates, if it seems too good to be true, it probably is.

Let this be, then, my one and only Public Service Announcement on Pressure-Sensitive Adhesive. Just say no, okay? It does not matter if the product says it’s archival. ‘Archival’ is an even vaguer marketing term than ‘organic’. Believe me, I understand the challenges of possessing an item in need of repair. The temptation to use a quick fix is strong. There are many book repair manuals out there that instruct on the use of tape–unfathomably. But, as common sense dictates, if it seems too good to be true, it probably is.

Books are really amazing. The more I repair and make them, the more respect and awe I have for the ones that stick around. I have seen and repaired many fine and treasured books, but the ones that amaze me most are the ones that seem the least likely to succeed. The Complete Poems of Paul Laurence Dunbar, despite all appearances, has “good bones”: it was sewn through folds and was printed on decent paper. And despite the copious use of tape by one of its previous owners, I was able to put it back together and give it a gentle push down the road. When things slow down, I may be able to give it some attempts at removing the tape, but for now, the tape will have to stay where it is, unfortunately.